Published: April 25, 2023

By: Piper Naudin, LSU Manship School News Service

BATON ROUGE, La. — Increasing violence in schools has prompted lawmakers to propose the “Protect Teachers Act,” a bill that would grant protection from criminal liability to teachers who try to break up student-on-student violence.

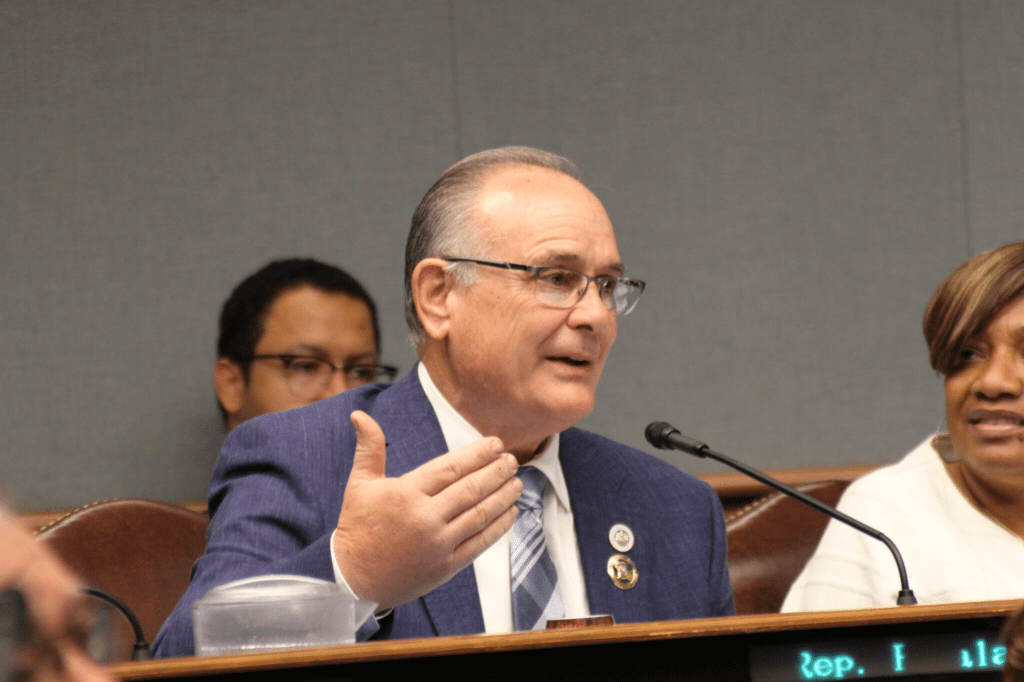

“Instead of watching two kids kill each other, this allows teachers to stop that from happening,” the bill’s primary author, Rep. Valarie Hodges, R-Denham Springs, told the House Committee on Civil Law and Procedure Monday.

The committee voted 11-0 to advance the bill, which would grant criminal immunity to teachers who use justifiable defense to stop battery and assault by one or more students. Teachers already have immunity from civil lawsuits when breaking up fights.

Hodges said she did not intend for the bill to protect teachers who abused students, stating that the immunity from criminal charges would apply only to teachers who did not have malicious intent.

Read more at WWL-TV